by Aditi Prasad – The ultimate summer parties happen at water holes in Indian jungles. Summers in India are infamous for high temperatures and sweltering heat. Water bodies in forests dry out causing animals to congregate at a few large water holes. Finding water in such conditions is similar to hitting a jackpot! One can find several different species of animals indulging in a jamboree of sorts.

The deer and the antelope are the most numerous attendees. In Ranthambore, a semi-arid dry deciduous forest where I conduct my field work, sambar and spotted deer are most commonly seen at water holes followed by nilgai and chinkara. The colours to the party are brought by our featured friends peafowl, parakeet, golden oriole, as well as the cinereous tit and silver bills. Bringing in the crazy are the langurs fighting and biting and cartwheeling over each other. They all drink water to their fill and cool off their bodies. Apart from hydration, animals here also access minerals through salts dissolved in the water or by licking rocks surrounding water holes. These salts are essential for the metabolism and growth of mammals1.

With the entry of a large carnivore the party comes to an end! With loud alarm calls the herbivores vacate the water hole. The langurs and the peacocks take to the trees. The tiger is the top predator in Ranthambore and is one of the few cat species that is fond of water. They tend to stay in the water for hours – as much as seven hours at a stretch! Leopard- the other large carnivore in Ranthambore- uses water holes sparsely, just to quench thirst in the early hours of morning or late in the day before starting its nocturnal life. Interestingly, owing to the high concentration of prey around water holes and salt licks, predators and hunters used the paths leading to these locations to track down prey or game2.

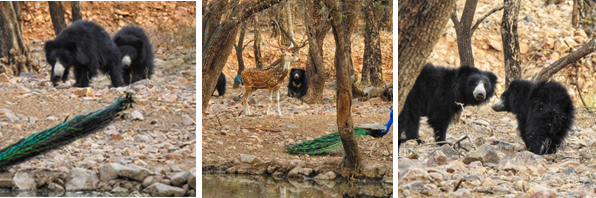

Several species reproduce in spring and summer and the jungle brims with motherly love. Grey francolins line the trails with mother and father followed by as many as 10 chicks, nests of golden orioles and lapwings grace the trees and banks. This was also the time I had a wonderful sighting of a sloth bear and its cub. Not only did I get to see the interactions of a mother and cub sloth bear, the whole sequence was incredibly heart-warming and is particularly memorable. While we stopped to fill water in our bottles at a meeting point, we noticed a sloth bear looking out from far away towards a water hole. It seemed to be afraid to come out with tourist vehicles around. As soon as the vehicles left, it came out accompanied by a timid cub. The cub was nervous to come out in the open- it seemed to be intimidated by the deer and peacocks around. The mother patiently (and in human terms, mutely) pacified and prodded the cub. It slowly and warily came to the water, stopping several times to observe and sniff its surroundings. On reaching the water, both mother and cub bent down to drink. The cub quickly lapped up water and trotted back to the hills finally breaking into a run! One would not have imagined a bear being scared of peacocks and deer but it seems you have to learn to be a bear! The image of this endearing cub is imprinted in my mind.

Covid-19 having struck India in the last two summers has kept away both wildlife researchers and admirers from studying and relishing our fascinating forests in the sultry heat. Hoping to a better year and getting back to the good old jungles .

References:

1. Abrahams, P. W. The Chemistry and Mineralogy of Three Savanna Lick Soils. J. Chem. Ecol. 1999 2510 25, 2215–2228 (1999).

2. A Brief History of Salt | Time. Available at: https://time.com/3957460/a-brief-history-of-salt/. (Accessed: 13th July 2021)